Nitrite

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Nitrite

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

dioxidonitrate(1−) | |||

| Other names

nitrite

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| NO− 2 | |||

| Molar mass | 46.005 g·mol−1 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Nitrous acid | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

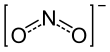

The nitrite ion has the chemical formula NO−

2. Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries.[1] The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name nitrite also refers to organic compounds having the –ONO group, which are esters of nitrous acid.

Production

[edit]Sodium nitrite is made industrially by passing a mixture of nitrogen oxides into aqueous sodium hydroxide or sodium carbonate solution:[2][1]

- NO + NO2 + 2 NaOH → 2 NaNO2 + H2O

- NO + NO2 + Na2CO3 → 2 NaNO2 + CO2

The product is purified by recrystallization. Alkali metal nitrites are thermally stable up to and beyond their melting point (441 °C for KNO2). Ammonium nitrite can be made from dinitrogen trioxide, N2O3, which is formally the anhydride of nitrous acid:

- 2 NH3 + H2O + N2O3 → 2 NH4NO2

Structure

[edit]

2, which contribute to the resonance hybrid for the nitrite ion

The nitrite ion has a symmetrical structure (C2v symmetry), with both N–O bonds having equal length and a bond angle of about 115°. In valence bond theory, it is described as a resonance hybrid with equal contributions from two canonical forms that are mirror images of each other. In molecular orbital theory, there is a sigma bond between each oxygen atom and the nitrogen atom, and a delocalized pi bond made from the p orbitals on nitrogen and oxygen atoms which is perpendicular to the plane of the molecule. The negative charge of the ion is equally distributed on the two oxygen atoms. Both nitrogen and oxygen atoms carry a lone pair of electrons. Therefore, the nitrite ion is a Lewis base.

In the gas phase it exists predominantly as a trans-planar molecule.

Reactions

[edit]Acid-base properties

[edit]Nitrite is the conjugate base of the weak acid nitrous acid:

Nitrous acid is also highly unstable, tending to disproportionate:

- 3 HNO2 (aq) ⇌ H3O+ + NO−

3 + 2 NO

This reaction is slow at 0 °C.[2] Addition of acid to a solution of a nitrite in the presence of a reducing agent, such as iron(II), is a way to make nitric oxide (NO) in the laboratory.

Oxidation and reduction

[edit]The formal oxidation state of the nitrogen atom in nitrite is +3. This means that it can be either oxidized to oxidation states +4 and +5, or reduced to oxidation states as low as −3. Standard reduction potentials for reactions directly involving nitrous acid are shown in the table below:[4]

Half-reaction E0 (V) NO−

3 + 3 H+ + 2 e− ⇌ HNO2 + H2O+0.94 2 HNO2 + 4 H+ + 4 e− ⇌ H2N2O2 + 2 H2O +0.86 N2O4 + 2 H+ + 2 e− ⇌ 2 HNO2 +1.065 2 HNO2+ 4 H+ + 4 e− ⇌ N2O + 3 H2O +1.29

The data can be extended to include products in lower oxidation states. For example:

- H2N2O2 + 2 H+ + 2 e− ⇌ N2 + 2 H2O; E0 = +2.65 V

Oxidation reactions usually result in the formation of the nitrate ion, with nitrogen in oxidation state +5. For example, oxidation with permanganate ion can be used for quantitative analysis of nitrite (by titration):

- 5 NO−

2 + 2 MnO−

4 + 6 H+ → 5 NO−

3 + 2 Mn2+ + 3 H2O

The product of reduction reactions with nitrite ion are varied, depending on the reducing agent used and its strength. With sulfur dioxide, the products are NO and N2O; with tin(II) (Sn2+) the product is hyponitrous acid (H2N2O2); reduction all the way to ammonia (NH3) occurs with hydrogen sulfide. With the hydrazinium cation (N

2H+

5) the product of nitrite reduction is hydrazoic acid (HN3), an unstable and explosive compound:

- HNO2 + N

2H+

5 → HN3 + H2O + H3O+

which can also further react with nitrite:

- HNO2 + HN3 → N2O + N2 + H2O

This reaction is unusual in that it involves compounds with nitrogen in four different oxidation states.[2]

Analysis of nitrite

[edit]Nitrite is detected and analyzed by the Griess Reaction, involving the formation of a deep red-colored azo dye upon treatment of a NO−

2-containing sample with sulfanilic acid and naphthyl-1-amine in the presence of acid.[5]

Coordination complexes

[edit]Nitrite is an ambidentate ligand and can form a wide variety of coordination complexes by binding to metal ions in several ways.[2] Two examples are the red nitrito complex [Co(NH3)5(ONO)]2+ is metastable, isomerizing to the yellow nitro complex [Co(NH3)5(NO2)]2+. Nitrite is processed by several enzymes, all of which utilize coordination complexes.

Biochemistry

[edit]

In nitrification, ammonium is converted to nitrite. Important species include Nitrosomonas. Other bacterial species such as Nitrobacter, are responsible for the oxidation of the nitrite into nitrate.

Nitrite can be reduced to nitric oxide or ammonia by many species of bacteria. Under hypoxic conditions, nitrite may release nitric oxide, which causes potent vasodilation. Several mechanisms for nitrite conversion to NO have been described, including enzymatic reduction by xanthine oxidoreductase, nitrite reductase, and NO synthase (NOS), as well as nonenzymatic acidic disproportionation reactions.

Uses

[edit]Chemical precursor

[edit]Azo dyes and other colorants are prepared by the process called diazotization, which requires nitrite.[1]

Nitrite in food preservation and biochemistry

[edit]The addition of nitrites and nitrates to processed meats such as ham, bacon, and sausages reduces growth and toxin production of Clostridium botulinum.[8][9] Sodium nitrite is used to speed up the curing of meat and also impart an attractive colour.[10] On the other hand, a 2018 study by the British Meat Producers Association determined that legally permitted levels of nitrite do not affect the growth of C. botulinum.[11] In the U.S., meat cannot be labeled as "cured" without the addition of nitrite.[12][13][14] In some countries, cured-meat products are manufactured without nitrate or nitrite, and without nitrite from vegetable sources. Parma ham, produced without nitrite since 1993, was reported in 2018 to have caused no cases of botulism.[10]

In mice, food rich in nitrites together with unsaturated fats can prevent hypertension by forming nitro fatty acids that inhibit soluble epoxide hydrolase, which is one explanation for the apparent health effect of the Mediterranean diet.[15] Adding nitrites to meat has been shown to generate known carcinogens; the World Health Organization (WHO) advises that eating 50 g (1.8 oz) of nitrite processed meat a day would raise the risk of getting bowel cancer by 18% over a lifetime.[10]

The recommended maximum limits by the World Health Organization in drinking water are 3 mg L−1 and 50 mg L−1 for nitrite and nitrate ions, respectively.[16] Ingesting too much nitrite and/or nitrate through well water is suspected to cause methemoglobinemia.[17]

95% of the nitrite ingested in modern diets comes from bacterial conversion of nitrates naturally found in vegetables.[18] However, potentially cancer-causing nitroso compounds are not made in the pH-neutral colon. They are mostly made in the acidic stomach.[19][20]

Curing of meat

[edit]Nitrite reacts with the meat's myoglobin by attaching to the heme iron atom, forming reddish-brown nitrosomyoglobin and the characteristic pink "fresh" color of nitrosohemochrome or nitrosyl-heme upon cooking.[21] In the US, nitrite has been formally used since 1925. According to scientists working for the industry group American Meat Institute, this use of nitrite started in the Middle Ages.[22] Historians and epidemiologists argue that the widespread use of nitrite in meat-curing is closely linked to the development of industrial meat-processing.[23][24] French investigative journalist Guillaume Coudray asserts that the meat industry chooses to cure its meats with nitrite even though it is established that this chemical gives rise to cancer-causing nitroso-compounds.[25] Some traditional and artisanal producers avoid nitrites.

Addition of ascorbic acid, erythorbic acid, or one of their salts enhance the binding of nitrite to the iron atom in myoglobin.[21] These chemicals also reduce the formation of nitrosamine in the stomach, but only when the fat content of a meal is less than 10%, beyond which they instead increase the formation of nitrosamine.[26][27]

Antidote for cyanide poisoning

[edit]Nitrites in the form of sodium nitrite and amyl nitrite are components of many cyanide antidote kits.[28] Both of these compounds bind to hemoglobin and oxidize the Fe2+ ions to Fe3+ ions forming methemoglobin. Methemoglobin, in turn, binds to cyanide (CN), creating cyanmethemoglobin, effectively removing cyanide from the complex IV of the electron transport chain (ETC) in mitochondria, which is the primary site of disruption caused by cyanide. Another mechanism by which nitrites help treat cyanide toxicity is the generation of nitric oxide (NO). NO displaces the CN from the cytochrome c oxidase (ETC complex IV), making it available for methemoglobin to bind.[29]

Organic nitrites

[edit]

In organic chemistry, alkyl nitrites are esters of nitrous acid and contain the nitrosoxy functional group. Nitro compounds contain the C–NO2 group. Nitrites have the general formula RONO, where R is an aryl or alkyl group. Amyl nitrite and other alkyl nitrites have a vasodilating action and must be handled in the laboratory with caution. They are sometimes used in medicine for the treatment of heart diseases. A classic named reaction for the synthesis of alkyl nitrites is the Meyer synthesis[30][31] in which alkyl halides react with metallic nitrites to a mixture to nitroalkanes and nitrites.

Safety

[edit]Nitrite salts can react with secondary amines to produce N-nitrosamines, which are suspected of causing stomach cancer. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises that each 50 g (1.8 oz) of processed meat eaten a day would raise the risk of getting bowel cancer by 18% over a lifetime; processed meat refers to meat that has been transformed through fermentation, nitrite curing, salting, smoking, or other processes to enhance flavor or improve preservation. The World Health Organization's review of more than 400 studies concluded in 2015 that there was sufficient evidence that processed meats caused cancer, particularly colon cancer; the WHO's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified processed meats as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).[10][32]

Nitrite (ingested) under conditions that result in endogenous nitrosation, specifically the production of nitrosamine, has been classified as Probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A) by the IARC.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Laue W, Thiemann M, Scheibler E, Wiegand KW (2006). "Nitrates and Nitrites". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_265. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 461–464. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ IUPAC SC-Database Archived 19 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine A comprehensive database of published data on equilibrium constants of metal complexes and ligands

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Ivanov, V. M. (1 October 2004). "The 125th Anniversary of the Griess Reagent". Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 59 (10): 1002–1005. doi:10.1023/B:JANC.0000043920.77446.d7. ISSN 1608-3199. S2CID 98768756.

- ^ Sparacino-Watkins, Courtney; Stolz, John F.; Basu, Partha (16 December 2013). "Nitrate and periplasmic nitrate reductases". Chem. Soc. Rev. 43 (2): 676–706. doi:10.1039/c3cs60249d. ISSN 1460-4744. PMC 4080430. PMID 24141308.

- ^ Simon, Jörg; Klotz, Martin G. (2013). "Diversity and evolution of bioenergetic systems involved in microbial nitrogen compound transformations". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1827 (2): 114–135. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.005. PMID 22842521.

- ^ Christiansen LN, Johnston RW, Kautter DA, Howard JW, Aunan WJ (March 1973). "Effect of nitrite and nitrate on toxin production by Clostridium botulinum and on nitrosamine formation in perishable canned comminuted cured meat". Applied Microbiology. 25 (3): 357–62. doi:10.1128/AEM.25.3.357-362.1973. PMC 380811. PMID 4572891.

- ^ Lee, Soomin; Lee, Heeyoung; Kim, Sejeong; Lee, Jeeyeon; Ha, Jimyeong; Choi, Yukyung; Oh, Hyemin; Choi, Kyoung-Hee; Yoon, Yohan (August 2018). "Microbiological safety of processed meat products formulated with low nitrite concentration — A review". Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 31 (8): 1073–1077. doi:10.5713/ajas.17.0675. ISSN 1011-2367. PMC 6043430. PMID 29531192.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Bee (1 March 2018). "Yes, bacon really is killing us". The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

In trade journals of the 1960s, the firms who sold nitrite powders to ham-makers spoke quite openly about how the main advantage was to increase profit margins by speeding up production.

- ^ Doward, Jamie (23 March 2019). "Revealed: no need to add cancer-risk nitrites to ham". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

The results show that there is no change in levels of inoculated C. botulinum over the curing process, which implies that the action of nitrite during curing is not toxic to C. botulinum spores at levels of 150ppm [parts per million] ingoing nitrite and below.

- ^ De Vries, John (1997). Food Safety and Toxicity. CRC Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8493-9488-1.

- ^ sodium nitrite and nitrate facts Accessed 12 Dec 2014

- ^ Doyle, Michael P.; Sperber, William H. (23 September 2009). Compendium of the Microbiological Spoilage of Foods and Beverages. Springer. p. 78. ISBN 9781441908261.

- ^ Charles, R. L.; Rudyk, O.; Prysyazhna, O.; Kamynina, A.; Yang, J.; Morisseau, C.; Hammock, B. D.; Freeman, B. A.; Eaton, P. (2014). "Protection from hypertension in mice by the Mediterranean diet is mediated by nitro fatty acid inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (22): 8167–72. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.8167C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402965111. PMC 4050620. PMID 24843165.

- ^ Bagheri, H.; Hajian, A.; Rezaei, M.; Shirzadmehr, A. (2017). "Composite of Cu metal nanoparticles—multiwall carbon nanotubes—reduced graphene oxide as a novel and high performance platform of the electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of nitrite and nitrate". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 324 (Pt B): 762–772. Bibcode:2017JHzM..324..762B. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.11.055. PMID 27894754.

- ^ Powlson DS, Addiscott TM, Benjamin N, Cassman KG, de Kok TM, van Grinsven H, et al. (2008). "When does nitrate become a risk for humans?". Journal of Environmental Quality. 37 (2): 291–295. Bibcode:2008JEnvQ..37..291P. doi:10.2134/jeq2007.0177. PMID 18268290. S2CID 14097832.

- ^ "Is celery juice a viable alternative to nitrites in cured meats?". Office for Science and Society. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Lee, L; Archer, MC; Bruce, WR (October 1981). "Absence of volatile nitrosamines in human feces". Cancer Res. 41 (10): 3992–4. PMID 7285009.

- ^ Kuhnle, GG; Story, GW; Reda, T; et al. (October 2007). "Diet-induced endogenous formation of nitroso compounds in the GI tract". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (7): 1040–7. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.011. PMID 17761300.

- ^ a b Pappenberger, Günter; Hohmann, Hans-Peter (2013). "Industrial Production of l-Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) and d-Isoascorbic Acid". Biotechnology of Food and Feed Additives. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. 143: 143–188. doi:10.1007/10_2013_243. ISBN 978-3-662-43760-5.

- ^ Binkerd, E. F.; Kolari, O. E. (1 January 1975). "The history and use of nitrate and nitrite in the curing of meat". Food and Cosmetics Toxicology. 13 (6): 655–661. doi:10.1016/0015-6264(75)90157-1. ISSN 0015-6264. PMID 1107192.

- ^ Coudray, Guillaume (2017). Cochonneries: Comment la charcuterie est devenue un poison (in French). Paris: La Découverte. pp. 40–70. ISBN 978-2-7071-9358-2.

- ^ Lauer, Klaus (1 January 1991). "The history of nitrite in human nutrition: A contribution from German cookery books". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 44 (3): 261–264. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(91)90037-A. ISSN 0895-4356. PMID 1999685.

- ^ "Guillaume Coudray on the Nitro Meat Cancer Connection". Corporate Crime Reporter. 14 April 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Combet, E.; Paterson, S; Iijima, K; Winter, J; Mullen, W; Crozier, A; Preston, T; McColl, K. E. (2007). "Fat transforms ascorbic acid from inhibiting to promoting acid-catalysed N-nitrosation". Gut. 56 (12): 1678–1684. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.128587. PMC 2095705. PMID 17785370.

- ^ Combet, E; El Mesmari, A; Preston, T; Crozier, A; McColl, K. E. (2010). "Dietary phenolic acids and ascorbic acid: Influence on acid-catalyzed nitrosative chemistry in the presence and absence of lipids". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 48 (6): 763–771. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.011. PMID 20026204.

- ^ Meillier, Andrew; Heller, Cara (2015). "Acute Cyanide Poisoning: Hydroxocobalamin and Sodium Thiosulfate Treatments with Two Outcomes following One Exposure Event". Case Reports in Medicine. 2015: 217951. doi:10.1155/2015/217951. ISSN 1687-9627. PMC 4620268. PMID 26543483.

- ^ Bebarta, Vikhyat S.; Brittain, Matthew; Chan, Adriano; Garrett, Norma; Yoon, David; Burney, Tanya; Mukai, David; Babin, Michael; Pilz, Renate B.; Mahon, Sari B.; Brenner, Matthew (June 2017). "Sodium Nitrite and Sodium Thiosulfate Are Effective Against Acute Cyanide Poisoning when Administered by Intramuscular Injection". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 69 (6): 718–725.e4. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.09.034. ISSN 0196-0644. PMC 5446299. PMID 28041825.

- ^ Victor Meyer (1872). "Ueber die Nitroverbindungen der Fettreihe". Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie. 171 (1): 1–56. doi:10.1002/jlac.18741710102.; Victor Meyer, J. Locher (1876). "Ueber die Pseudonitrole, die Isomeren der Nitrolsäuren". Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie. 180 (1–2): 133–55. doi:10.1002/jlac.18761800113.; V. Meyer and Stüber (1872). "Vorläufige Mittheilung". Chemische Berichte. 5: 203–05. doi:10.1002/cber.18720050165.; Victor Meyer, O. Stüber (1872). "Ueber die Nitroverbindungen der Fettreihe". Chemische Berichte. 5: 399–406. doi:10.1002/cber.187200501121. S2CID 95188274.; Victor Meyer, A. Rilliet (1872). "Ueber die Nitroverbindungen der Fettreiche. Dritte Mittheilung". Chemische Berichte. 5 (2): 1029–34. doi:10.1002/cber.187200502133.; Victor Meyer, C. Chojnacki (1872). "Ueber die Nitroverbindungen der Fettreihe. Vierte Mittheilung". Chemische Berichte. 5 (2): 1034–38. doi:10.1002/cber.187200502134.

- ^ Robert B. Reynolds, Homer Adkins (1929). "The Relationship of the Constitution of Certain Alky Halides to the Formation of Nitroparaffins and Alkyl Nitrites". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 51 (1): 279–87. Bibcode:1929JAChS..51..279R. doi:10.1021/ja01376a037.

- ^ Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, et al. (December 2015). "Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat". The Lancet Oncology. 16 (16): 1599–1600. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1. PMID 26514947. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Grosse Y, Baan R, Straif K, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Cogliano V (August 2006). "Carcinogenicity of nitrate, nitrite, and cyanobacterial peptide toxins". The Lancet Oncology. 7 (8): 628–629. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70789-6. PMID 16900606. Retrieved 13 October 2024.