Froebel gifts

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

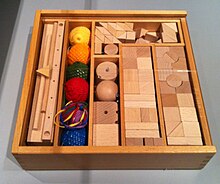

The Froebel gifts (German: Fröbelgaben) are educational play materials for young children, originally designed by Friedrich Fröbel for the first kindergarten at Bad Blankenburg. Playing with Froebel's gifts, singing, dancing, and growing plants were each important aspects of this child-centered approach to education. The series was later extended from the original six to at least ten sets of gifts.[1][2]

Description

[edit]

The Sunday Papers (Sonntagsblatt) published by Fröbel between 1838 and 1840 explained the meaning and described the use of each of his six initial "play gifts" (Spielgabe): "The active and creative, living and life producing being of each person, reveals itself in the creative instinct of the child. All human education is bound up in the quiet and conscientious nurture of this instinct of activity; and in the ability of the child, true to this instinct, to be active."[3][better source needed]

Between May 1837 and 1850, Froebel's gifts were made in Bad Blankenburg in the principality of Schwarzburg Rudolstadt, by master carpenter Löhn, assisted by artisans and women of the village.[4] In 1850, production was moved to the Erzgebirge region of the Kingdom of Saxony in a factory established for this purpose by S F Fischer.[5]

Fröbel also developed a series of activities ("occupations") such as sewing, weaving, and modeling with clay,[1] for children to extend their experiences through play. Ottilie de Liagre[who?] in a letter to Fröbel in 1844[citation needed] observed that playing with the Froebel gifts empowers children to be lively and free, but people can degrade it into a mechanical routine.

Each of the first five gifts was assigned a number by Fröbel in the Sunday Papers, which indicated the sequence in which each gift was to be given to the child.[citation needed]

Gift 1 (infant)

[edit]The first gift is a soft ball or yarn ball in solid color, which is the right size for the hand of a small child. When attached to a matching string, the ball can be moved by a mother in various ways as she sings to the child. Although Fröbel sold single balls, they are now usually supplied in sets of six balls consisting of the primary colors: red, yellow, and blue; as well as the secondary colors: purple, green, and orange. These soft balls can be squashed in the hand, and they revert to their original shapes.[citation needed]

The first gift was intended by Fröbel to be given to very young children. His intention was that, through holding, dropping, rolling, swinging, hiding, and revealing the balls, the child may acquire knowledge of objects and spatial relationships, movement, speed and time, color and contrast, and weights and gravity.[6]: 42

Gift 2 (1–2 years)

[edit]The second gift originally consisted of two wooden objects, a sphere and a cube. Fröbel called this gift "the child's delight", since he observed the joy of each child discovering the differences between the sphere and cube.

The child is already familiar with the shape of the wooden sphere, which is the same as the ball of the first gift. The wooden sphere always looks the same when viewed from any direction. Like the child, the wooden sphere is always on the move. When rolled on a hard surface, the wooden sphere produces sounds. In contrast, the wooden cube is the surprise of the second gift. It remains where it is placed, and from each direction presents a different appearance.

The second gift was developed to enable a child to explore and enjoy the differences between shapes. By attaching a string or inserting a rod in a hole drilled through these wooden geometric shapes, they can be spun by a child. Although the sphere always appears the same, the spinning cube reveals many shapes when spun in different ways. This led Fröbel to later include a wooden cylinder in the second gift, which may also be spun in many different ways.

Gift 3 (2–3 years)

[edit]The familiar shape of the cube is now divided into eight identical beechwood cubes, about one inch along each edge, which is a convenient size for the hand of a small child. A child delights in pulling apart this gift, rearranging the eight cubes in many ways, and then reassembling them in the form of a cube. This is the first building gift.

Gift 4 (2–3 years)

[edit]This second building gift at first appears the same as in Gift 3. But a surprise awaits the child when the pieces are pulled apart. Each of these eight identical beechwood blocks is a rectangular plank, twice as long and half the width of the cubes of the previous gift.[1] Many new possibilities for play and construction arise due to these differences.

Gift 5 (3–4 years)

[edit]This building gift consists of more cubes, some of which are divided in halves or quarters.

Gift 6 (4–5 years)

[edit]A set of more complex wooden blocks that includes cubes, planks, and triangular prisms.[1]

Influence

[edit]Froebel's gifts were adapted by Caroline Pratt for the school, which she founded in 1913 in the Greenwich Village district of New York City. This school embodied a child-centered approach to education. Children worked together to reconstruct their experiences through play. Based on the ideas of Friedrich Fröbel, the curriculum was drawn from the environment of the child; observations about the neighborhood inspired each child to reflect on their world directly so that they could make sense of their experiences.[7]

Joachim Liebschner commented in his book, A Child's Work: Freedom and Guidance in Froebel's Educational Theory and Practice "Realising how the Gifts were eventually misused by Kindergarten teachers who followed after Fröbel, it is important to consider what Fröbel expected the gifts to achieve. He envisaged that the Gifts will teach the child to use his (or her) environment as an educational aid; secondly, that they will give the child an indication of the connection between human life and life in nature; and finally, that they will create a bond between the adult and the child who play with them".[8]

Design and Architecture

[edit]Froebel's gifts and occupations, originally developed for children, have found great relevance in the fields of design and architecture. The gifts, which break down geometric forms and relations within the natural world, provide an opportunity to engage in two critical aspects of the design process: the exploration of language and the practice of play.[9][10]

Language

Froebel's gifts break down and synthesize the natural world into a simplified and approachable language. This process parallels the typical design process, where complex and multidimensional ideas are deconstructed into fundamental elements that can then be explored and manipulated to create something new.[10] Fröbel's sequential introduction of his gifts and occupations in increasing levels of abstraction and complexity provides a systematic approach to the exploration of form and relations, a skill necessary for the iterative and re-iterative nature of design.[11]

Play as a Design Tool

Froebel's gifts also offer a framework for play, an activity that is known to increase creative productivity and potential.[12] Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga's concept of play, as defined in Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture, articulates the following:

Summing up the formal characteristics of play we might call it a free activity standing quite consciously outside "ordinary" life as being "not serious", but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly. It is an activity connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner. It promotes the formation of social groupings which tend to surround themselves with secrecy and to stress their difference from the common world by disguise or other means. [13]

Play occurring within its own time and space, or "magic circle" suspended in reality, encourages experimentation and open ended creation without constraints of practical outcomes or judgement. By engaging in open-ended play with Froebel's gifts, designers have the opportunity to enter a state of free exploration. [14] Comparable to the way a baby babbles, this free exploration, or play, offers a critical formative opportunity for designers to freely explore the language of design.[10] Unlike traditional prototyping or ideation which is often tied to expectations and constraints of a real-world project, play removes any external pressures and enables creative experimentation that may otherwise not occur.[12]

Historical Influences

[edit]Fröbel's building forms and accompanying games were forerunners of abstract art as well as a source of inspiration to the Bauhaus movement.[15][16] Many modernist architects were exposed as children to Fröbel's ideas about geometry, including Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Buckminster Fuller.[16] Wright was given a set of the Fröbel's blocks at about age nine, and in his autobiography he cited them indirectly in explaining that he learned the geometry of architecture in kindergarten play:

For several years I sat at the little kindergarten table-top ruled by lines about four inches apart each way making four-inch squares; and, among other things, played upon these ‘unit-lines’ with the square (cube), the circle (sphere) and the triangle (tetrahedron or tripod)—these were smooth maple-wood blocks. All are in my fingers to this day.[17]: 359

Wright later wrote, "The virtue of all this lay in the awakening of the child-mind to rhythmic structures in Nature… I soon became susceptible to constructive pattern evolving in everything I saw."[18]: 25 [19]: 205 This statement provides insights into the value that Wright saw in Froebel's gifts within the context of design; they aided in developing an understanding of cause and effect that reached beyond comprehension and provided a means to design as opposed to recreate mere imitations of nature.[10]

The pedagogy of Froebel’s gifts even reached artists and designers who did not have direct interactions with them, as the concept of perceiving and relating to the world through a child-like innocence and naivety became a hallmark of 20th century art and design. The Basic Course of the Bauhaus included introductions to and interactions with basic forms, materials, colours and compositions in a very similar way to Froebel’s gifts and occupations. The primary designer of the Basic Course, Johannes Itten, had in fact been a primary school teacher and intentionally sought to stimulate students’ creativity within the course through a return to primitive exploration common in childhood.[10]

Current availability

[edit]Froebel gifts continue to be used in early childhood education in Korea and Japan, where they are made from local timber.[citation needed]

Reproduction sets can be ordered via the Internet.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Quinn, Suzanne Flannery. "Froebel's Gifts". Froebel Trust. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ a b "Intro to the Froebel Gifts". froebelgifts.com. Froebel USA. Archived from the original on 2022-12-11. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ "Sonntagsblatt – Froebel Decade". 17 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ "Fröbelspur Bad Blankenburg – Froebel Decade". 15 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ "About Us – Fröbelgaben". Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ Norman, Brosterman (1997). Inventing Kindergarten. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-9070-9.

- ^ The British Association for Early Childhood Education. "Friedrich Froebel | Early Education". www.early-education.org.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Liebschner, Joachim (2002). A child's work: freedom and play in Froebel's educational theory and practice. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press. ISBN 9780718830144.

- ^ Provenzo, Eugene F. (2009). "Friedrich Froebel's Gifts: Connecting the Spiritual and Aesthetic to the Real World of Play and Learning". American Journal of Play. 2 (1): 85–99. ISSN 1938-0399.

- ^ a b c d e dos Santos, B. K. (2012). (rep.). Toys within art, architecture and design: the case of Charles and Ray Eames. https://www.academia.edu/26094523/toys_within_art_architecture_and_design_the_case_of_Charles_and_Ray_Eames

- ^ Wilson, Stuart (1967-12-01). "The Gifts of Friedrich Froebel". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 26 (4): 238–241. doi:10.2307/988449. ISSN 0037-9808.

- ^ a b Power, P. (2011). Playing with Ideas: The affective dynamics of creative play. American Journal of Play, 3(3), 288–323.

- ^ Huizinga, J. (1960). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. The Beacon Press. [p.13]

- ^ Ham, Derek A. (2016-10-01). "How Designers Play: The Ludic Modalities of the Creative Process". Design Issues. 32 (4): 16–28. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00413. ISSN 0747-9360.

- ^ Frederick M. Logan, Kindergarten and Bauhaus, College Art Journal, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Autumn, 1950), pp. 36–43

- ^ a b "Froebel's Gifts". 99% Invisible. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- ^ Alofsin, Anthony (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright—the Lost Years, 1910–1922: A Study of Influence. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-01366-9.

- ^ Lange, Alexandra (2018). The design of childhood : how the material world shapes independent kids. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1632866356.

- ^ Hersey, George (2000). Architecture and Geometry in the Age of the Baroque. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32783-3.